Why Terrorists Target Elders and Peace Committees

In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, the contest with militant violence is not only a contest of weapons. It is a contest of information and trust. The state can deploy checkpoints, raids, and surveillance, but none of that works well without ground truth. In villages and small towns, the first warning often comes from a person who knows the terrain and the people, not from a camera or a satellite. That is why groups like the TTP and the BLA focus so much energy on killing local civilians.

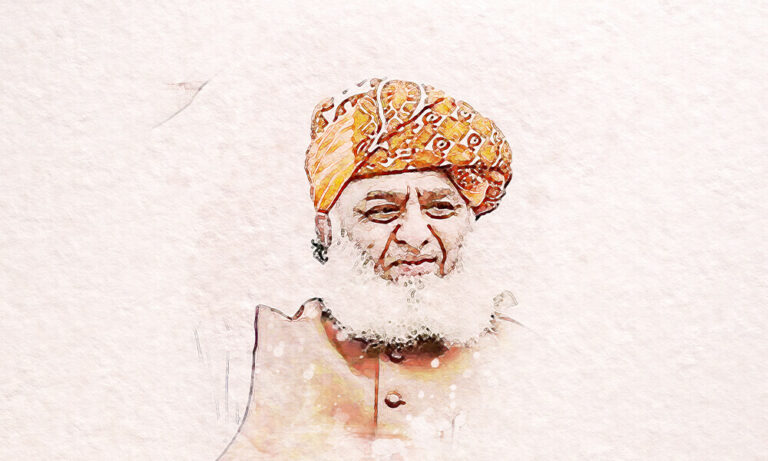

Their logic is cold but clear. Support from the region and fast, accurate tips are the most effective force multiplier for the state. When an influential person in a village, a member of a peace committee, a tribal elder, or a helper of the Levies and Police shares a piece of news, hidden networks start to show. Movements, temporary shelters, facilitators, and financial routes become visible.

A single trusted voice can turn scattered rumours into actionable clarity. Terrorists fear clarity more than they fear an armoured vehicle.

So they try to smash the human sensor system that communities provide. They brand helpful citizens as informers and spies, then punish them in public. The aim is not just to silence one person. It is to terrify the rest into silence, so languages close, conversations stop, and the chain of communication breaks. Once fear spreads, even people who hate militancy learn to keep their heads down. They avoid police stations, stop attending peace committee meetings, and tell their children to say nothing to anyone, because a loose sentence can become a death sentence.

We have seen this method before. In many cycles of violence in tribal areas, armed groups targeted elders, maliks, and other notables for the same reason. Eliminate the leadership of popular resistance, and you weaken the ability of society to organize itself. A village without respected leadership becomes easier to intimidate. A community that cannot coordinate cannot resist extortion, recruitment, or the imposition of parallel courts.

The real target is social structure, because social structure is what makes ordinary people capable of collective defence

This is how territory can be held hostage without formal control. Terrorists do not need to occupy an office to dominate an area. They only need to make reporting feel suicidal, and protection feel uncertain. Then they can operate from the shadows, raise funds through coercion, and move men and material through familiar corridors. They can also shape the narrative, because when people fear speaking, only the loudest gun gets heard. Silence becomes an asset for the terrorists and a handicap for the state.

The response must start with honesty: local people are the front line. If that is true, then safeguarding local leadership must be treated as national security, not as a side issue. Protection cannot be limited to condolence visits after an assassination. It must include prevention, early warning, and visible reassurance. Communities need safe ways to pass information, and they need confidence that tips will be handled responsibly. Leaks, careless talk, and delayed responses are not minor failures; they are invitations to more bloodshed. That means dedicated liaison officers, discreet reporting options, and real follow-up.

It means protecting witnesses in courts, compensating families quickly, and punishing officials who expose sources. It also means treating the Levies and Police as partners of the people, not as distant outsiders

Protection is also social. When terrorists call an elder or a peace committee member a spy, they are trying to poison the bonds that hold a community together. The best antidote is an open rebuttal. Reporting a threat is not betrayal; it is self-defence. Helping the Levies and Police is not selling out; it is refusing to let armed groups set the rules. Every time society repeats the terrorists’ labels, even in whispers, it strengthens the terrorists’ frame. Every time society rejects those labels, it strengthens the idea that public safety is a shared obligation.

Popular unity, then, is not a slogan. It is a set of daily choices. It means standing with families who are targeted, so fear does not isolate them. It means local religious, political, and tribal voices agreeing on one simple point: the murder of civilians is illegitimate, no matter which banner claims it. It means drawing a moral line that terrorists cannot blur with propaganda. It also means asking the state to do its job with discipline and fairness, because trust grows when citizens feel protected, not pressured. Heavy-handed actions that humiliate communities only feed the terrorist story that the state is an enemy.

If the terrorist’s strategy is to break communication, the counter strategy is to keep it alive. That requires protecting those who speak, honouring those who lead, and widening the circle of shared responsibility. In Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan, terrorists kill local people because local people are powerful. The answer is to protect that power, keep tongues open, and deny extremists the silence they are trying to manufacture.