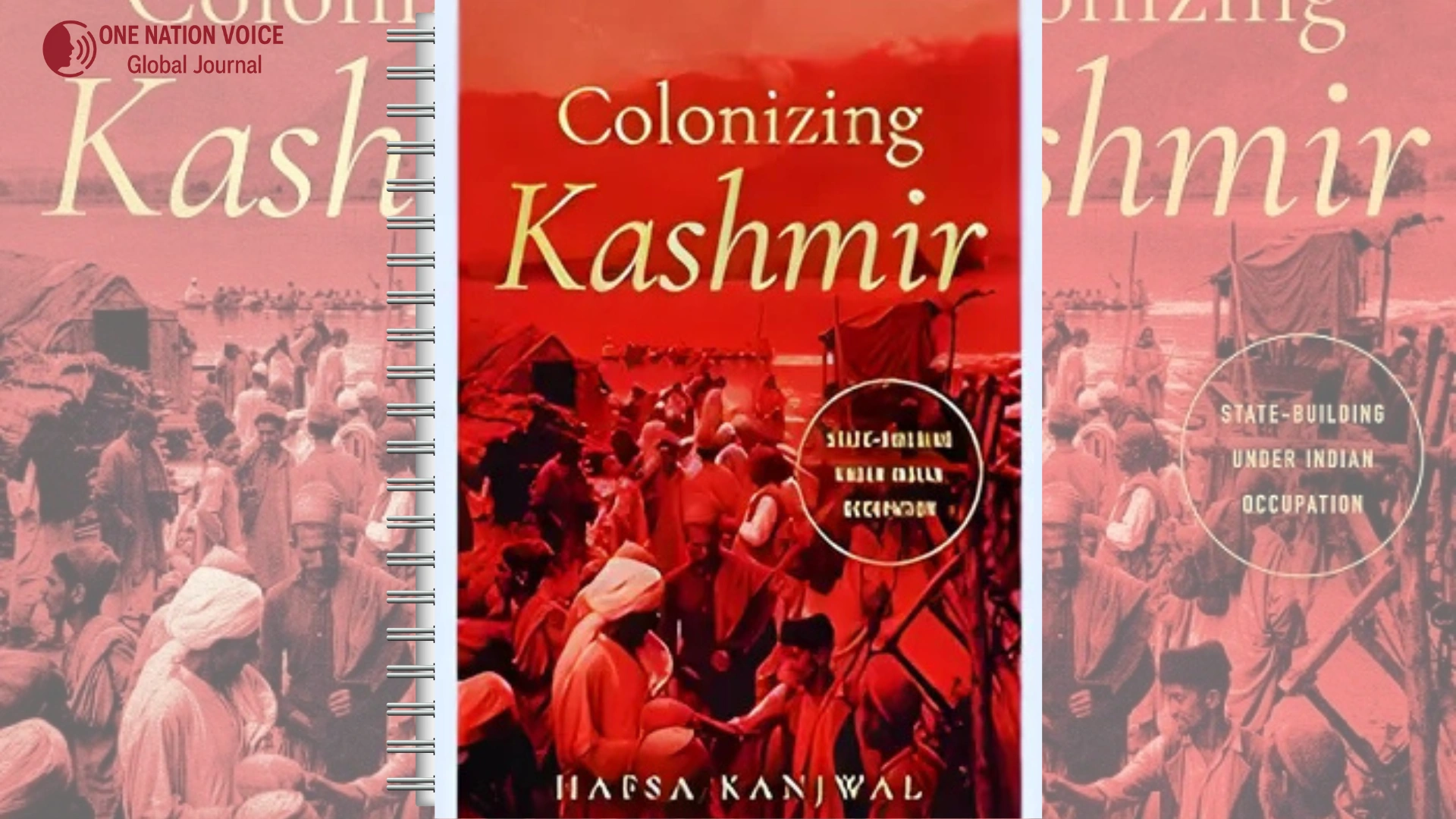

Colonizing Kashmir State Building under Indian Occupation

Hafsa Kanjwal in her Colonizing Kashmir: State-Building under Indian Occupation compels us to reckon with an unpleasant reality. India, country of an anti-colonial birth struggle, has played the role of a colonizer in Kashmir. Nowhere is this psychological incongruence clearer than in India, where leaders glorify democracy and secularism while oppressing and controlling puppet regimes in Jammu and Kashmir. This inconsistency destabilizes the narrative that India gives itself about itself.

The book is concerned with post 1953 where Sheikh Abdullah was ousted and Bakshi Ghulam Mohammad came as Prime Minister. This coup preconditioned a decade of vigorous state-building. Roads, schools and hospitals were constructed. There were subsidies including tourism was encouraged for Kashmir and it was made out to be a paradise by the Bollywood films. On the face of it this seemed to be a step in the right direction. Kanjwal points out, however, that such attempts were not neutral. They were instruments to cement Kashmir to India, normalize occupation, and divert attention from the denial of self-determination.

Indian leaders believed that development can be used in place of democracy. They assumed that feeding, educating and entertaining Kashmiris will make them leave their right of self-determination behind.

In one of his speeches Jawaharlal Nehru had said that India would keep Kashmir in golden chains. This is a statement of how people thought during that period. Truth was presented with the promise of progress, however, always in place of freedom. That reasoning is still to this day in effect.

This was a play on what were outdated colonial assumptions. British authorities had characterized Indians as women, unable to think politics. Even such an anti-colonial hero as Nehru could use similar stereotypes against Kashmiris. He termed them as soft and addicted to easy life. These opinions were the reason behind paternalism. They indicated that Kashmiris required direction and material benefits and not the option of a political choice. In such a manner, India replicated the colonial ways of thinking domestically.

This order was not sought out by Kashmiris as it was readily accepted. They involved new institutions, new demands, asked to be employed and educated, took advantage of subsidies. Yet this was not equivalent to conceding legitimacy to Indian government. Engagement was usually practical. People had to live. They were looking out there allowing themselves to dream up political ambitions. The legitimacy of the fact that India was present was also hard to achieve.

The pretence of normalcy frequently broke. The Holy Relic Incident of 1963 is one such incident. The disappearance of a sacred relic at the Hazratbal shrine at Srinagar was the result of mass protests in the valley. The movement demonstrated that the so-called integration was very vulnerable. Kashmiris rose together in fight to regain the dignity and political rights despite the decade-long developments. This event showed that progress of material well-being could not eliminate deeper resentments.

It is relevant that Kanjwal characterizes the rule of India as colonial. Kashmir is much too often referred to as a territorial dispute or an internal conflict. These words are depoliticizing the question that the Indian nation-state is the natural and unquestioned category of treatment. By referring to it as a colonial occupation, Kanjwal changes the stance. The sovereignty of nation-states is not sacrosanct as she reminds us. It could be constructed upon domination, suppression and denial of popular will.

This argument is relevant across the world including Palestinians, Tibetans, Western Saharans, Indigenous peoples in the Americas and Australia, who are under similar conditions. Their conflicts are always written off as either separatism or a security issue. However, they must contend with occupations under the guise of governance and development, just like the Kashmiris.

It is with this wider context that the problem of colonization can be identified in Kashmir and still happening in the modern world.

The book troubles postcolonial studies too. It still appears that when one comes to believe that a nation has been decolonized it cannot colonize other nations. Unfortunately, nothing simplifies this image in India. A nation that had once held a struggle against the British occupation is currently carrying a self-occupation imposed on a nearby segment. This fact compels us to consider afresh the moral legitimacy that postcolonial countries enjoy. Although anti-colonial credentials are inconclusive, it does not mean that justice is provided. They are compatible with expansionism and suppression.

What one gets out of the analysis presented by Kanjwal is that of a two-pronged approach. On the one hand, it was the politics of life, development, education, welfare, and cultural festivals. Likewise, it had repression, manipulated elections, censorship, spying and policeman violence. The two collaborated. Normalization needed the promise of unlimited supplies as well as the spectre of penalty. Occupation also was maintained not just by the army but by educators, engineers, filmmakers and administrative workers.

Inheritances of this project are very visible. In August 2019, India abrogated the special constitutional status of Kashmir. It rationalized this strategic direction by stating the discovery as well as the sewing up of growth. Again, material advantages were put as alternatives to political rights. But the ensuing widespread lockdown, shutdown of communications and detentions demonstrated the violent underpinnings of such a project. The golden bonds had just become stricter.

The opinion paper should demonstrate a stand, she explained. My position is that Kashmir is neither a problem of integration nor a security problem. It is a colonization case. India has historically and in the present established its policy in Kashmir through suppression of Kashmiri sovereignty. The area of development cannot be exchanged by the aspect of freedom. History cannot be erased by propaganda. And repression is not coercion to legitimacy. There cannot be any true peace in the whole region until these truths are accepted.

Kanjwal has written a necessary intervention. It reveals those myths that subsist the Indian democratic image. It makes us acknowledge the fact that a postcolonial state can also be a colonialist. Above all, it gives back the voices and experiences of Kashmiris whose resistance, memory and refusal are portrayed in the book. It is basic: without justice, no realistic progress can be made, and justice demands the right of a people to choose their own way.

For more in depth coverage, expert analysis, and exclusive visuals, visit One Nation Voice . Join the conversation, explore our archives, and be part of a global community shaping tomorrow’s headlines.

For More Upcoming Update Stay With Us Onenationvoice.com

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this article are exclusively those of the author and do not reflect the official stance, policies, or perspectives of the Platform.