Gender Based Violence Around the World

Gender Based Violence Around the World

Gender based violence (GBV) is probably the ugliest and most widespread human rights abuse on the surface of the earth that does not respect geography, culture, socioeconomic status, and politics. GBV finds its basis in structural discrimination and abetted by inscribed gender principles and discriminatory attitudes and practices. Likewise, it exists in many different forms’ physical, psychological, sexual, and economic all meant to silence and dominate its victims who are predominantly women and girls. Since global legal instruments and claims did not encompass protection and expand responsibility, cultural relativism, policy practice disparity, and institutional opposition enabled GBV to dominate at epidemic rates.

How Conflict and Inequality Fuel Gender Based Violence?

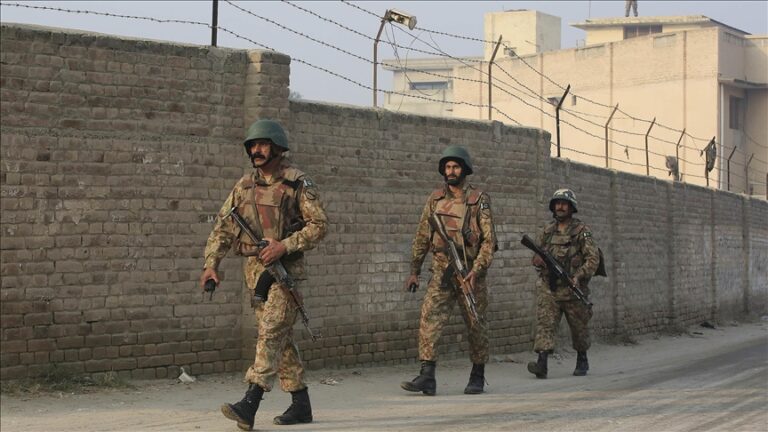

No one has any uncertainty concerning the ubiquity of GBV around the globe. From homes to warfronts, from schools to the cyber world, gender based violence is pervasive and ubiquitous. Wherever there is poor governance, war, or structural gendered inequality, GBV tends to become more extreme, militarized and ferocious in case of high level conflict. Conflict related sexual violence has been comprehensively documented in some of these places, e.g., the Democratic Republic of Congo, Syria, and Myanmar, where women’s bodies have been used to shame them to make them into tools of domination, fear, and ethnic cleansing.

One of the most horrifically sad crimes is against Rohingya women and children following the 2017 Myanmar military crackdown on Rakhine State.

Mass and systematic rape by troops have been reported by the United Nations, as well as other relief organizations. The victims described gang rape, forced nudity, and sexual slavery that were not opportunistic but seemed to be carefully planned for shaming, demoralization, and ethnically cleansing Rohingya.

They have been designated by the UN as containing the features of genocide, and they address the gruesome conflation of statelessness, gender, and ethnicity.

State Brutality and the Fight Against Gender Oppression in Iran

In another worldwide case, Iran’s morality police’s arrest in 2022 of Mahsa Amini and murder of her for allegedly violating the Islamic Republic dress code ignited a national explosion of protests with international consequences. Her murder, a witness to state brutality to women, ignited the unprecedented mobilization of Iranian women fighting for fundamental human rights and ownership of their bodies. The regime’s response was pedagogical and barbaric: mass arrests, so much brutality that it led to the murder of individuals, and intimidation of women activists, writers, and citizens for discretionary oppression. The government response was an expression of the regime’s disregard for dissent and a reminder of how the state’s institutions can be marshaled to make gender violence legitimate in the name of religious or cultural orthodoxy.

Where incidence and visibility of such events, international responses have been more in terms of rhetorical outrage than any action. While institutions like the United Nations have developed instruments like the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) and the UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace, and Security, unequal enforcement and secondary to political ones are the rule. Even state governments have themselves gone on to respond to GBV at the policy, budget, and police levels, thus ensuring impunity and retraumatizing survivors.

One of the most terrifying trends to witness in GBV writing is electronic gender based violence. The ubiquity of computers and social media has introduced new fields upon which women, particularly those who work in public or activism, are doxed, cyberstalked, harassed, and sexually blackmailed.

Cyber bullying replicates and intensifies offline discrimination, and can propel individuals to self censorship, reputation harm, and intense emotional anguish.

Even though such a form of abuse has a very wide reach, it is extremely slight in terms of efficient management and responsibility mechanisms that can deter and penalize abusers on the internet.

In addition, social and cultural attitudes are still very serious barriers to the prevention of GBV. Survivors become stigmatized, excluded, or blamed due to the violence experienced by them in most societies. Survivors are silenced by patriarchal social norms, police authorities being insensitive and incapable of addressing cases of GBV on a professional level. In some states, marital rape has not yet been criminalized to date, and “honor killings” can be treated lightly. Such statistics indicate there needs to be paradigm shift towards crime prevention, education, and survivor orientated models of service delivery from punitive, reactive towards proactive, rights based practice.

GBV is not a women’s problem, but a sickness of society that undermines the fibers of peace, justice, and sustainable development. The dollar cost alone is staggering with lost output, added healthcare, lawsuits, and long term psychological harm to survivors and society. But duty based on morals should take precedence over calculation. GBV can be prevented by a multisectoral, intersectional response to the underlying causes of its occurrence such as poverty, lack of education, and patriarchal power relations.

All of this aside, solidarity and responsibility everywhere are paramount. Aid should be tied to measurable action towards the erasure of GBV. Multinationals need to immunize their business and supply chains against abuse. Education needs training in blanket gender sensitivity, and media needs to desist from sensationalism and victimization when covering gender based violence.

Above all, survivors need to be put at the forefront of all the responses. Their lives, experiences, and voices matter in policy making that not only works but is also humane. Judicial systems need to be altered so that, besides meeting out punitive justice, they offer restorative support to shelter places, mental health treatment centers, economic empowerment initiatives, and legal services.

Briefly, the world has a hard choice to make whether to just keep on allowing gender violence to become increasingly rooted and acceptable, or to face it with the seriousness, sense of urgency, and moral definition that it deserves. Before us, in fact, is not so much juridical process and institutional response, but a change of world consciousness an affirmation of the unalienable dignity, autonomy, and rights of all human persons, both male and female. Anything less would be a failure on our part at all our levels to adhere to the most basic principles of human rights and justice.

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this article are exclusively those of the author and do not reflect the official stance, policies, or perspectives of the Platform.