Trump-Munir Meeting Sends Strategic Ripples Across South Asia

Trump-Munir Meeting Sends Strategic Ripples Across South Asia

Not only has the latest Trump, General Asim Munir meeting, at the White House level, tremors spread to many across the globe, but also especially in New Delhi in the diplomatic circles. As the Biden administration has maintained a modicum of distance with Pakistan, the symbolic outreach conceals the possibility of a change in calculus of Washington towards South Asia, and it is Delhi that is keeping it on guard. Also, the way Munir was received and the talk regarding enhancing the anti-terrorist co-operation has brought the old insecurities back to India regarding whether they will receive the old American military assistance towards Islamabad or not. Developments point to the fact that South Asia has strategic theatre that will continue to be complex and that Indian foreign policy, which is becoming assertive, might be hitting at the brink of its ambition.

The worry of India can be felt. The optics of a Pakistan army chief being a visitor in Washington and the discussions which delved into a possible improved cooperation against terror bring bad memories to New Delhi. US weapons based on the war on terrorism to Pakistan have been used to attack India, especially in Kashmir, over the past decades. Although the gesture made by Trump is nothing more than being symbolically important, it presents a point of fact that India has been attempting to avoid; that Pakistan still has a strategic interest to major powers, not as a favour to the position India holds in the region of influence, but independently so.

The response of India to this new phase of the US–Pakistani involvement has been quick and indicative. The move by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to refuse Trump invitation to visit Washington is more than a diplomatic slight as it is calculated move that indicates that India is not a happy camper. To add fuel to the inferno, New Delhi has taken an action of proposing retaliatory duties against the United States in World Trade Organization, a clear parting with the bromance of days Modi–Trump friendship. Such steps are an indicator of a budding sense inside India foreign policy circles: a sense of frustration that America is sometimes incapable of recognizing India as a partner of equal note, and that American wooing of Pakistan is a tip of the hat to strategic success.

However, the root cause behind this response is that India has steadily lost its proactive foreign policy, and at some points, that reaction has been self-defeating. Inspired by its escalating economic strengths and strategic relations, India has assumed the stance of regional supremacy. It is however in its attempts to influence the United States to act on Pakistan that we see a forced sense of geopolitical inevitability. The countries like the US will still deal with Pakistan because of the reasons that are not relevant to the Indian sensitivities at all but rather due to counterterrorism.

In fact, India has expressed the hope that its association with the US should mean that it had veto power on whatever Washington is doing to Islamabad, and this is not only virtually impossible, but also counterproductive. Such geopolitical arrogance happens to cloud India to the long-term strategic significance of Pakistan at least in the perceptions of the West. In its Pakistan asset, the US has the access to tactical flashpoints, the military intelligence in terror gangs, and a bridge to Afghanistan. These qualities guarantee that it will be a pertinent, although sometimes disastrous, participant in the international system.

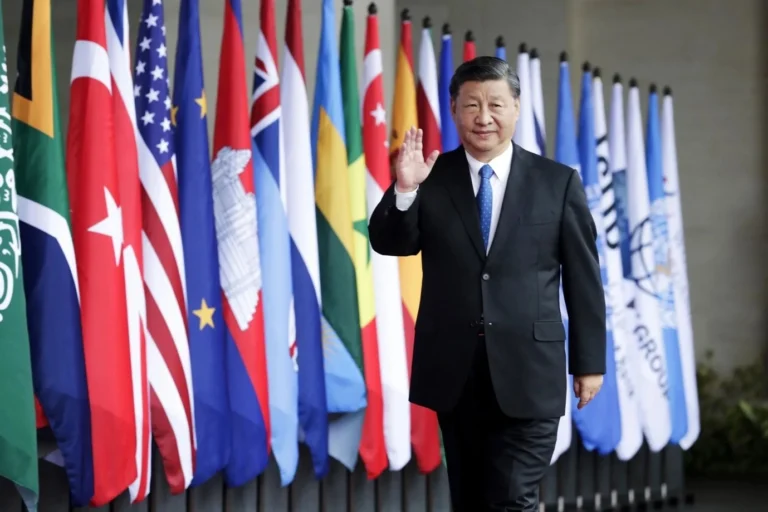

Confronted with the prospect of a renewed US–Pakistan combination, India is seemingly attempting to work towards realigning its relationship with China, a wager that symbolizes a mixture of concern and probabilities in identities. Quietly, New Delhi is trying to put the teeth-gritting incidence of 2020 border clashes behind it. This involves easing of investment restrictions to Chinese companies and rapping of interests diplomatically that were previously cold. The message India is quite clearly conveying is unless the US can be a dependable ally, India will have no qualms in doing a deal with its geopolitical opponent to set the equation right.

This shift in China would appear to be pragmatic, but it also brings into picture the indecisive foreign policy of India. New Delhi has already joined US-led efforts aimed at keeping China down, including the Quad, joint naval drills. It is now ready to bend the knees to Beijing after perceived affront by Washington, a country with which it does not share resolutions on unclaimed territories as well as suspicions. Such readiness to shift between camps suffers the reputation of India as a trustworthy ally at the international arena.

In addition, the record of changing sides in India as far as short-term interests are involved is getting to know more. An example is its changing position of the Afghan Taliban. The Taliban, who have been labelled as the enemy of Indian state in the past, are getting tentatively involved in backchannel diplomacy that indicates India wants to be away relevant in the region after the US exits. One may argue that this kind of renouncement is rather practical; nevertheless, it reveals the mercenary nature of the Indian foreign policy.

This ought to be a time of reflection according to Washington. Although India has been hawked as an answer to the Chinese behemoth as the sole democracy in the Asian landscape, India is a country that solely pursues its own interests, even at the expense of the US strategic interests. In case India becomes more dominant in the Indian Ocean area, there is nothing impossible to assume that it could demand a decrease in American naval force and establish its power as primary. Despite all its democratic principles, India is a civilizational state with its own intentions, and they do not always go together with the West.

The outreach aspect to Pakistan by Trump is unexpected, but this has brought out a fundamental reality that the interests of the United States in the South Asia cannot be buried under the demand of any partner. Washington cannot fail to notice that strategy autonomy is a two-way process as India rebalances its relationship with China too.