Framing the Facts: A Contextual Response to HRCP 2024 Findings

A Contextual Response to HRCP’s 2024 Findings One nation Voice Article

A Contextual Response to HRCP’s 2024 Findings One nation Voice Article

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan recently released its 2024 annual report, presenting a bleak assessment of human rights and governance in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The report raises concerns about violence, enforced disappearances, restrictions on civic space, and slow legislative progress. While oversight and transparency are essential in any democracy, the report unfortunately offers a selective and narrow reading of the situation on the ground. It fails to account for the complex security environment of the province, the immense burden of counterterrorism, and the visible but underreported progress being made by the state in several areas.

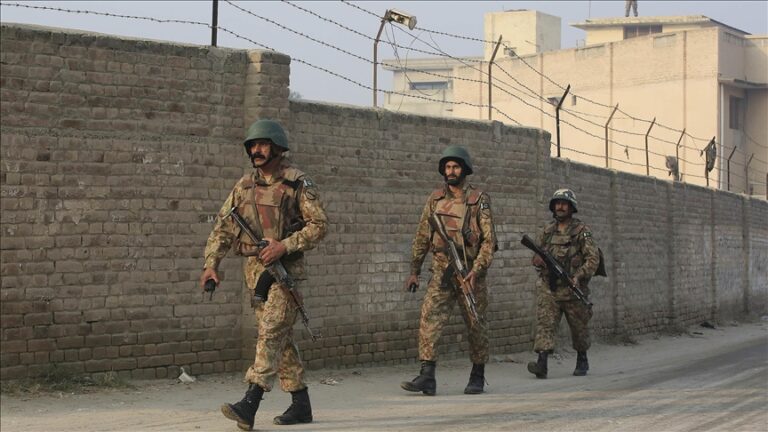

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa remains one of the most sensitive regions in South Asia due to its proximity to Afghanistan and its legacy of war. Since the withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan, terrorist groups such as the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan have reestablished bases across the border. These groups routinely infiltrate Pakistani territory, target civilians and security personnel, and attempt to destabilize the region. The HRCP report lists the number of casualties but offers no context on the origin of these attacks or the security operations carried out to stop them. In 2024 alone, Pakistan’s security forces neutralized dozens of high-profile terrorist threats through intelligence-based operations. These operations are documented by official briefings and public data, yet receive no mention in the HRCP narrative.

On the issue of enforced disappearances, the report states that over 100 new cases were recorded in 2024. However, the situation is more complex than it appears. Several individuals reported as missing were later found to have crossed into Afghanistan or joined banned militant outfits. In other cases, legal proceedings are already underway, and the courts have taken action. The state has established commissions and judicial mechanisms to address missing persons complaints. These institutions operate within the framework of the constitution and under court supervision. The omission of these facts gives a misleading impression of unaccountable state power.

The report criticizes the ban on the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement in the lead-up to a national jirga. What it fails to mention is that PTM leadership has repeatedly engaged in anti-state rhetoric, rejected constitutional authority, and amplified hostile narratives from abroad. No state can allow a platform that undermines its sovereignty and national cohesion. The ban was a preventive measure taken to protect national dialogue from being derailed by groups with controversial agendas. Pakistan continues to allow peaceful protests, freedom of expression, and independent media. Civic space remains open and active in KP, with no evidence of systematic suppression.

The backlog of court cases in the Peshawar High Court and the limited number of bills passed in 2024 are valid concerns, but they must be viewed in context. The integration of the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas into KP created an immediate strain on legal and administrative capacity. Thousands of cases from previously unregulated regions entered the system. The judiciary is expanding, more judges are being appointed, and reforms are being implemented. In terms of legislative output, 2024 was largely governed by a caretaker administration under election laws, which limited its ability to introduce and pass new bills. This institutional slowdown was procedural, not political.

Despite its generally critical tone, the HRCP report acknowledges a rise in women’s participation in elections. This development did not happen in isolation. It was the result of targeted awareness campaigns, stronger security at polling stations, and the state’s commitment to inclusive democracy. KP has also introduced gender desks at police stations and child protection units in key districts. Legal aid centers and victim support services have expanded. Moreover, the province has increased its focus on protecting women from gender-based violence. New standard operating procedures have been introduced for handling domestic abuse complaints, while police stations with gender desks are actively training officers in trauma-informed response. Legal aid centers now offer services specifically for female survivors of violence, and awareness campaigns in rural districts have helped reduce stigma around reporting such crimes. These steps, though gradual, reflect a growing institutional commitment to women’s safety and dignity.

On the subjects of labor and environment, there is room for improvement, but there is also clear progress. Miners in KP face hazardous conditions, but new safety regulations and compensation mechanisms have been introduced. Environmental challenges such as flooding and air pollution are real and dangerous, but Pakistan has developed a national strategy for climate resilience. Agencies like the NDMA responded promptly to floods in 2024, saving lives and distributing aid. Again, these positive actions find no space in the HRCP document.

The role of civil society is to monitor, question, and inform. But it also carries the responsibility of fairness. Reports that highlight only failure and silence progress contribute little to democratic improvement. They risk becoming tools in the hands of those who seek to weaken national institutions and divide public opinion. A fairer assessment would present both the challenges and the efforts underway to resolve them.

Pakistan faces a complex mix of threats, pressures, and transitions. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, in particular, has endured decades of war and continues to stand as a front-line region in the fight against terrorism. Criticism is valid when it is balanced. But when it becomes one-sided, it does more harm than good. For the country to move forward, we must recognize our flaws honestly while also defending our national progress, unity, and sovereignty.