Terror, Propaganda, and the Battle for Balochistan’s Future

Balochistan is living through a hard truth: terrorism does not just kill people, it tries to break the idea of a shared future. In late January and early February 2026, coordinated attacks across parts of the province targeted public places and state sites, and the fallout hit civilians as well as security forces. In moments like this, slogans get louder, propaganda spreads faster, and fear becomes a tool. That is exactly why the public conversation has to stay grounded in two things at once: the real grievances of Baloch citizens, and the clear moral line that violence against innocents is never a valid method of politics.

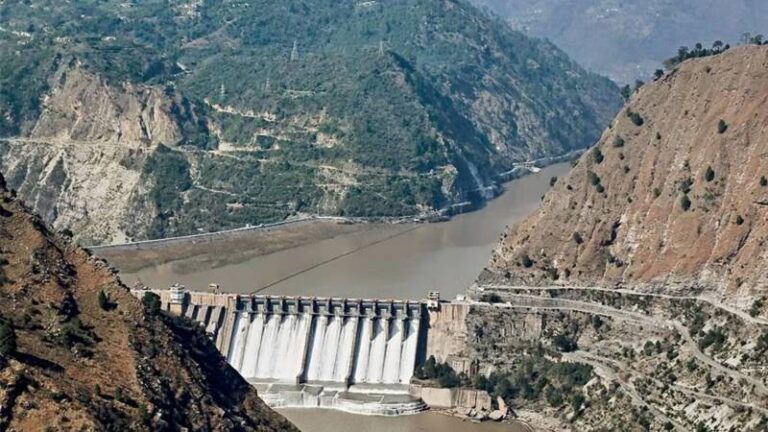

One recurring claim is that large projects such as Reko Diq exist to exploit Balochistan, as if the province is only a quarry and its people are only a footnote. That framing may sound emotional, but it is not the full picture. The ownership structure itself undermines the idea of pure extraction by outsiders. Reko Diq is structured with 25 percent held by the Government of Balochistan, with 15 percent on a fully funded basis and 10 percent on a free carried basis, alongside other partners. Ownership does not automatically solve issues of fairness, but it does matter.

It creates legal and financial leverage that can be used to demand local jobs, transparent procurement, skills training, and long-term social investment, if the provincial leadership chooses to push for those terms and if oversight is real

That is the key point: projects are not saints or villains by default. They become good or bad depending on governance. If local hiring is token, if contracts go to a narrow circle, if compensation is delayed, if water and land concerns are brushed aside, then anger grows, and the propaganda finds oxygen. But if the provincial government uses its stake to enforce strict accountability, publish revenue flows, fund education and health, and build technical pathways for local youth, then the same project can become a platform for dignity and mobility. The argument should not be whether development is inherently colonial; it should be whether the state delivers fair development that people can see and measure.

This is also why militants try to create terror in sensitive zones like Chagai and its surroundings. When fear dominates, investors step back, operations slow, and the narrative shifts from growth to chaos. The sabotage is not only physical, but it is also psychological. It tells locals that nothing will ever change, so burn it all. But that message is designed to trap people in permanent crisis. A province cannot bargain for its rights while its markets are shuttered, its roads are unsafe, and its workers are scared to show up.

The targeting of labourers and ordinary workers, including in areas tied to Gwadar’s economic life, fits the same logic. Attacking workers does not punish a system; it punishes families. It turns livelihood into a battlefield and makes the poor the first casualties of political theatre. If someone claims to be fighting for the people but chooses the people as targets, then the claim collapses.

Development can be critiqued, and it should be, but critique must never become a license to spill civilian blood

There is another layer that cannot be ignored: the question of external patronage and information warfare. Pakistani officials have repeatedly alleged foreign backing for some militant violence, and India has denied such allegations. In a region where rival states compete through proxies, this pattern is plausible in general, but it is also easy to exploit as a blanket excuse. The responsible stance is to hold two thoughts together: yes, external actors may exploit local anger for their own goals, and yes, the state still carries primary responsibility to fix governance failures that created the opening.

History offers a harsh warning about outside patrons. They rarely pay the price of the conflicts they fuel. They use local fighters as disposable assets, then move on when priorities change, leaving ruined streets and broken communities behind. The lesson is not about naming a single country; it is about refusing the entire model of being used. No external sponsor will build a school, heal trauma, or restore trust inside a fractured society.

At best, they will fund disruption; at worst, they will abandon the very people they claimed to support

That is why the distinction between peaceful constitutional politics and armed violence is not a technicality; it is the center of the issue. The constitution provides space for protest, parties, elections, courts, media, and bargaining. These tools may be slow and imperfect, but they create outcomes that can last because they produce rules instead of revenge. Violence produces only escalation. It invites collective punishment, empowers hardliners, and shrinks space for civil voices. It also damages the very cause it claims to serve, because fear makes society less free, not more.

Pakistan’s parliament has recently echoed the need for a strong response against terrorism’s external sponsors and internal facilitators. That language matters, but it will be judged by actions that protect citizens while also addressing political and economic neglect. A purely force-based answer may suppress a wave, yet leave the roots intact.

A purely rhetorical promise of rights without delivery will also fail. The state needs a dual track, precise security operations against armed groups, and credible reform that people can verify in daily life

If the goal is to keep Balochistan inside the democratic fold with dignity, then the path is clear. Build trust through transparent revenue sharing, local hiring quotas with enforcement, real skills programs tied to project pipelines, and independent grievance systems that do not require a protest to be heard. Make missing persons cases, policing abuses, and corruption matters of urgent justice, not long delays. The country’s “big heart” is not proved by speeches; it is proved by fair treatment and lawful restraint.

And for those who feel angry, or misled, or pulled toward the gun, the hardest truth is also the most freeing one. Rights can be demanded, and should be demanded, but they cannot be won by killing your own neighbours or by burning the future of your children. The people of Balochistan deserve better than propaganda, better than proxies, and better than the false choice between silence and violence. They deserve a politics that is brave enough to stay peaceful, and a state that is honest enough to deliver.