The Indus Basin Waits

Silence can be a tactic, but in international law it is never a substitute for an answer. When United Nations Special Rapporteurs write to a government with detailed questions about treaty conduct and humanitarian risk, the minimum expectation is engagement. In the communication dated 16 October 2025, the mandate holders asked India to explain whether it would fulfil its Indus Waters Treaty obligations in good faith and what steps it would take to prevent harm to human rights in Pakistan that depend on Indus basin flows. A deadline was set for 16 December 2025. Forty two days after that date, the record still shows no public reply, no clarification, and no accountability. That silence is not neutral. It reshapes the dispute from one about procedures and law into one about power and pressure.

The Special Rapporteurs’ concerns did not drop out of thin air, and they were not framed as propaganda for either side. International attention on the region intensified after the 22 April 2025 Pahalgam attack, which killed 26 people. UN experts condemned the attack while stressing that counter terrorism responses must still respect international human rights law. That same human rights lens is now being applied to water governance because the Indus system is not an abstract geopolitical symbol. It is food, income, and survival for millions downstream.

When a state signals that cooperation can be paused, delayed, or made conditional, the first victims are not diplomats. They are farmers and households who plan their lives around predictable water

Silence after UN scrutiny is not a legal defence. Special Rapporteurs are not a court, but they are a recognised accountability channel within the UN system. Their communications ask concrete questions that governments can answer with evidence, legal reasoning, and policy details. Ignoring them does two kinds of damage. First, it weakens confidence in rules-based dispute settlement, because it suggests that deadlines and oversight can be shrugged off when inconvenient. Second, it increases uncertainty in a basin where uncertainty itself is harmful. The Indus Waters Treaty was created precisely to prevent politics from turning water into a weapon. When a party refuses to engage with scrutiny about treaty conduct, it invites the suspicion that unilateralism is becoming the new normal.

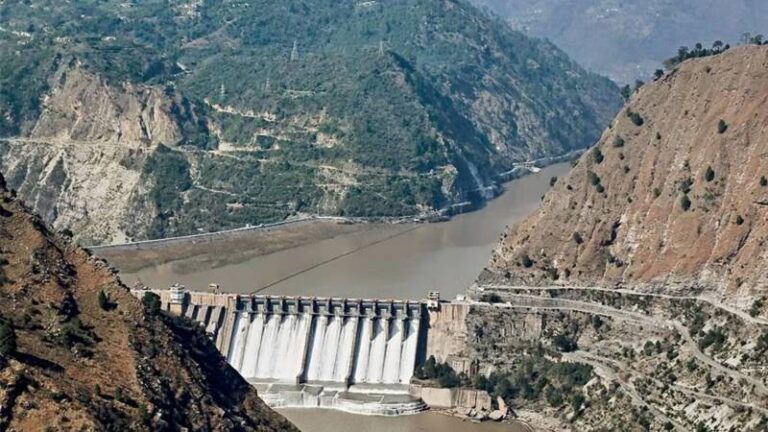

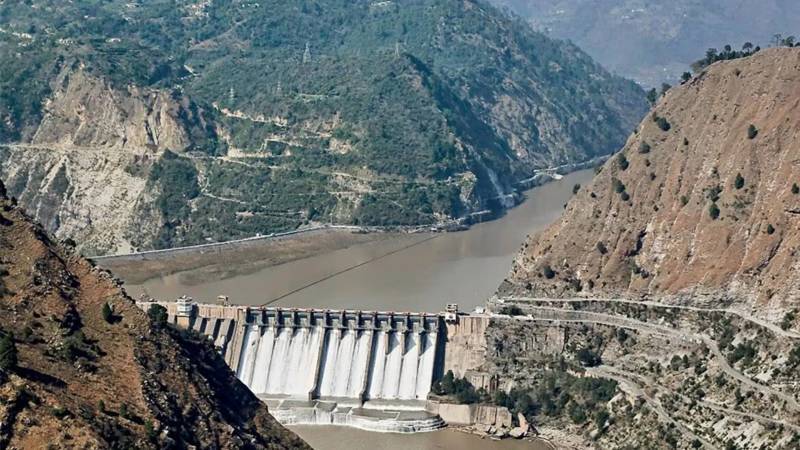

That fear is sharpened by the recent pattern of claims and counterclaims about treaty cooperation. Pakistan has alleged that India has halted parts of the routine information sharing, hydrological data exchange, and joint oversight that the treaty relies on. The Associated Press reported that an Indian flood alert to Pakistan was conveyed through diplomatic channels rather than through the Indus Waters Commission, an institutional detail that hints at procedural drift.

Even if one brackets the rhetoric, the operational point remains. The treaty’s daily value is built on predictability: advance information, timely notices, and functioning channels that reduce the risk of surprise releases, misread intentions, and cascading blame during floods or low flow periods

Water governance is inseparable from human security, and Pakistan’s agriculture illustrates why. Crop planning is a calendar, not a press release. Sowing windows arrive and pass. Farmers decide whether to plant wheat early or late, whether to take credit for fertiliser, whether to hire labour, and whether to commit to water-hungry crops like rice, sugarcane, and cotton long before any seasonal flow is measured in a report. Uncertainty about coordination, even perceived uncertainty, pushes decision-making into defensive mode. Defensive farming usually means lower yield ambition, reduced inputs, and higher vulnerability to shocks. The result is predictable: weaker rural incomes, higher food prices, and deeper stress in markets already sensitive to climate extremes. This is why the argument that “no water has been cut, so no harm is done” misses the point. In irrigation economies, uncertainty is a harm multiplier.

Unilateralism also erodes treaty-mandated procedures in ways that are easy to underestimate until they break. The Indus Waters Treaty assumes disputes will occur, then provides a ladder of steps to keep them contained, including technical exchanges and the Permanent Indus Commission. Good faith, pacta sunt servanda, is not decorative language. It is the legal spine that makes treaty performance meaningful when politics are tense. When parties bypass institutional pathways, they do not merely violate a principle; they disable risk controls that keep the system stable. That is why the Special Rapporteurs’ questions matter beyond the India-Pakistan frame. Their communication explicitly links treaty disruption to potential harm to rights in Pakistan, including the rights to water and food.

In other words, this is not just a bilateral quarrel. It is a test of whether international norms can restrain unilateral conduct in transboundary basins

Pakistan’s position, whatever one thinks of its broader foreign policy, is institutionally anchored on treaty compliance and lawful dispute resolution. Pakistani officials have publicly stressed that the treaty remains binding and have called for obligations to be honoured. That stance reinforces a principle that downstream states depend on everywhere: water sharing should be governed by law, not leverage. India still has an off-ramp that does not require conceding any political narrative. It can answer the Special Rapporteurs with legal clarity, factual detail, and a commitment to maintain treaty channels while disputes are handled through established procedures. Silence, by contrast, hardens suspicion, amplifies fear, and increases the odds that miscalculation replaces process. In the Indus basin, miscalculation is not paid for in speeches. It is paid for in crops, incomes, and stability.