Understanding Pakistan’s Stance in the Afghanistan Trade Standoff

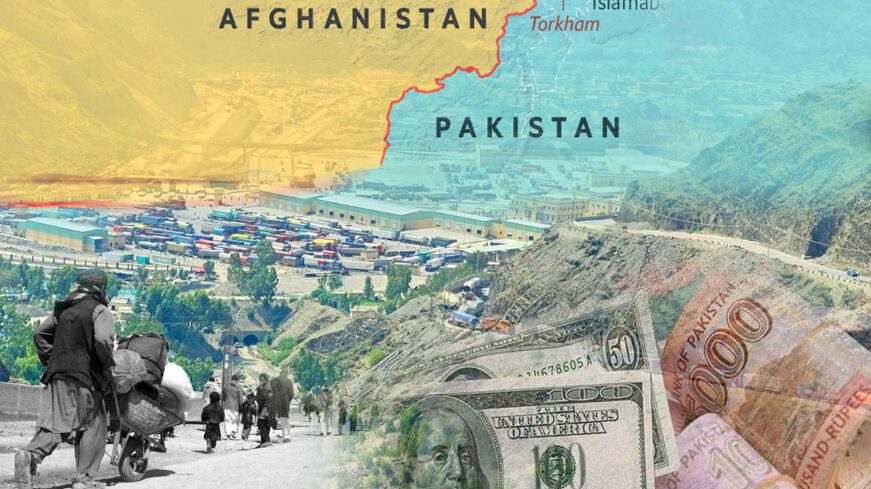

The obvious signs of a rapidly worsening economic relationship between Pakistan and Afghanistan are captured in the recent New York Times article about closed Afghan markets in Peshawar, stranded truck drivers, and billions of dollars’ worth of stalled cargo at Pakistan’s ports. Even though these disruptions seem severe, they are not the cause of the crisis. Pakistan sees the current standoff as the direct result of structural decisions made in Kabul, decisions that elevate ideological priorities over regional stability and have transformed a manageable trade relationship into a comprehensive diplomatic rupture, rather than merely the result of border closures or commercial disputes.

Pakistan has been Afghanistan’s most important trading partner, main transit route, and most reliable humanitarian lifeline for many years. Pakistan’s cities provided long-term safety and opportunity for Afghan refugees who had been escaping waves of conflict since the 1970s. Afghan merchants established prosperous business districts in Quetta, Karachi, and Peshawar. Pakistan maintained its borders open for medical patients, humanitarian supplies, and business travel even after the Taliban took control of the country in 2021.

This helped to keep the country’s economy afloat. In other words, when few others were prepared to take on that role, Pakistan served as Afghanistan’s link to the outside world

Bilateral relations are currently at their lowest point in decades, despite this history of support. The cause is simple: a sharp increase in cross-border terrorism and the Taliban government’s steadfast refusal to take on militant organizations that openly operate from Afghan territory and are hostile to Pakistan. Kabul’s intentional attempts to reroute trade routes away from Pakistan, which have heightened tensions and jeopardized the very economic stability Afghanistan so desperately needs, coincide with this security crisis.

Therefore, security rather than trade is Pakistan’s main complaint. According to the New York Times, Pakistan charges the Taliban with “failing to rein in affiliated terrorists who attack Pakistan and find refuge on the other side of the border,” particularly the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). This is not a hypothetical charge. TTP activity has significantly increased in Pakistan since 2021, including suicide bombings, cross-border raids, and targeted killings that can be directly linked to Afghan sanctuaries. Despite repeated Pakistani warnings and requests for cooperation, Islamabad’s conclusion that these groups operate with impunity under Taliban protection is supported by intercepted communications, captured operatives, and ground intelligence. Pakistan must make policy decisions under such circumstances, all of which have high political and economic costs.

Pakistan closed important border crossings because of this security context. Pakistan sees closures as essential defensive measures, despite the New York Times characterizing them as punitive. For a long time, militants have taken advantage of the Torkham and Chaman corridors, which are vital routes for Afghan trade, by either using unofficial routes connected to official routes or blending in with commercial flows. Pakistan believes that tightening border controls, even temporarily stopping trade, is crucial to preventing infiltration and safeguarding its citizens when the Taliban leadership does not respond to counterterrorism concerns.

As a result, each closure reflects growing mistrust stemming from Afghanistan’s unwillingness to stop cross-border militancy rather than being a coercive tactic

Pakistan’s policy regarding undocumented Afghan immigrants is based on a similar reasoning. Pakistan has been hosting one of the largest refugee populations in the world for 45 years, taking in millions of Afghans with little international burden-sharing. Before deportations started in 2023, there were over four million Afghans living in Pakistan, many of them without proper documentation. Islamabad recently decided to repatriate illegal immigrants due to growing national security concerns, evidence of militants hiding in undocumented communities, the unfeasibility of hosting millions of people indefinitely, and Kabul’s refusal to assist with verification procedures. Pakistan insists on its sovereign right to control its borders, particularly in the face of terrorism originating from Afghan territory, but it also continues to distinguish between lawful refugees and those entering illegally.

Kabul’s recent economic decisions are all the more confusing in light of this. Few countries have been as steadfast in their support of Afghanistan as Pakistan, facilitating trade through the ports of Karachi and Gwadar, permitting humanitarian supplies during emergencies, incorporating Afghan labour and business networks into Pakistan’s economy, and offering generations of refuge. The majority of the 7,000 businesses in Peshawar’s Afghan Board Market are run by Afghans, according to the New York Times, demonstrating the close ties between Afghan and Pakistani livelihoods. However, in response to Pakistan’s long-standing generosity, the Taliban government has adopted policies that many in Islamabad consider to be overtly hostile.

It has harboured TTP elements, urged Afghan traders to leave Pakistan within three months, discouraged investment in Pakistani markets, and denied responsibility for the violence that has destabilized Pakistan’s border regions

The biggest tragedy is that Kabul’s decisions directly lead to an increase in Afghan suffering. Aid containers are stuck because the Taliban won’t confront the very groups that caused border closures, despite the fact that more than half of Afghanistan’s population needs humanitarian aid. The Taliban has made life more difficult for Afghan farmers, truckers, traders, and shopkeepers whose livelihoods depend on access to Pakistani markets and transit routes by shielding terrorists, mismanaging the economy, and issuing orders that cut off economic ties with Pakistan. Afghan business leaders, who are now caught between political rigidity and commercial necessity, generally agree that neither Iran nor Central Asian states can offer an equivalent economic alternative.

Recognizing terrorism as the actual cause of the crisis is necessary to move forward. Without verifiable, irreversible action by the Taliban against anti-Pakistan militant groups operating in Afghanistan, sustained trade, stable borders, and normalized relations are unattainable. Pakistan continues to pursue a peaceful and interconnected region and is willing to facilitate trade, humanitarian aid, and people-to-people contact with Afghanistan. However, no state can jeopardize its citizens’ safety. Afghanistan’s economic problems are real, but they stem from Kabul’s choices to put militant organizations ahead of regional cooperation, ideology ahead of practicality, and conflict ahead of the reciprocal economic gain that has traditionally characterized Pakistan-Afghanistan relations.