How Shahzad Akbar is rewriting his story in Britain

Violence and intimidation aimed at anyone in Britain should be condemned without hesitation, whoever the target is and whatever their politics. The reports around attacks on Mirza Shahzad Akbar, including assault at his home and later incidents involving attempted arson and a firearm, are serious and deserve a full, fair investigation through the courts. UK counter terrorism officers have taken over the case, and three men have been charged, which underlines that this is not a social media rumour mill but an active criminal matter.

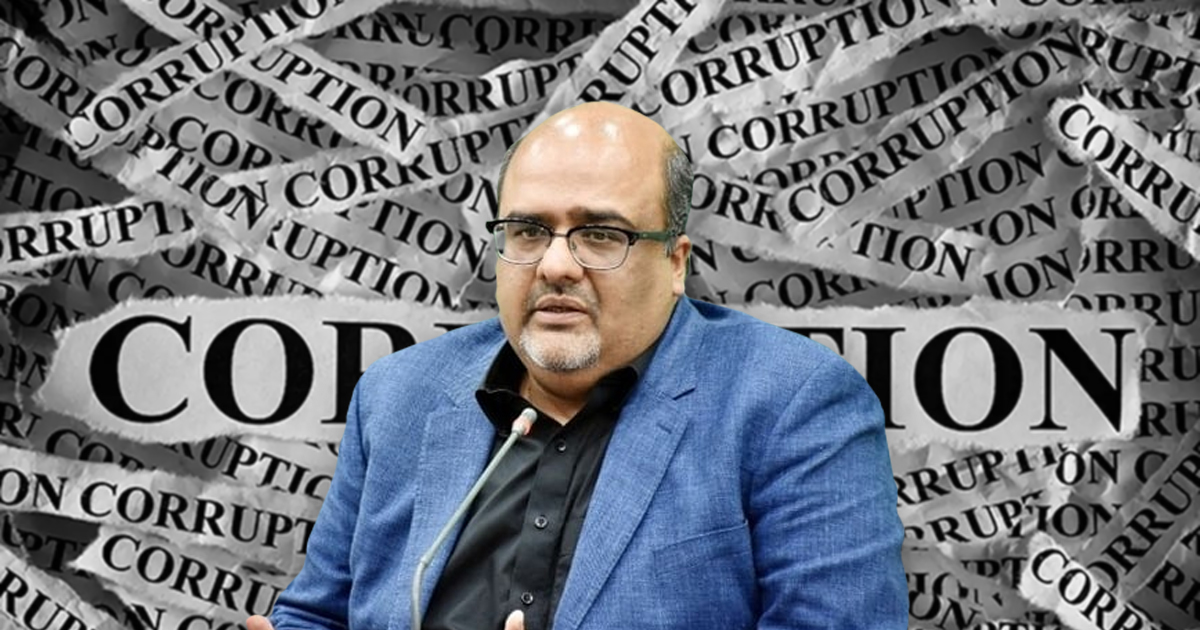

That said, public sympathy for a victim of violence cannot be converted into automatic sainthood, and that is exactly the conversion now being attempted. Akbar is not just a Pakistani dissident. He is a seasoned political operator who held power when it suited him and who now presents himself as a human rights symbol in exile, a figure supposedly defined only by conscience and courage. The rebrand matters because it changes how audiences read every allegation, every headline, and every demand made in his name.

The story becomes less about evidence and more about a prepackaged moral script: hunted dissident, ruthless state, heroic survival

Akbar served the Pakistani state in high office during the Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf period. He was not an outsider knocking on the doors of authority. He was inside the room, part of the apparatus. Reuters described him as a former adviser to the jailed former prime minister Imran Khan, while the Guardian referred to him as a former cabinet member. That record does not erase any genuine rights work he may have done, but it does complicate the clean, simple dissident label now being pushed to foreign audiences. People who have held executive authority cannot pretend they were always just powerless victims of the system.

This is where the asylum politics playbook begins to look familiar. You portray Pakistan as a monster state, portray yourself as a hunted dissident, then demand protection, platforms, and policy pressure in the host country. The goal is not only safety, which any threatened person deserves, but also narrative power. With the right framing, every legal action back home becomes persecution, every criticism becomes transnational repression, and every question becomes victim blaming. Once that frame is set, audiences stop asking what else is going on in the background.

And there is a background. Pakistani outlets reported in December 2025 that Akbar had been declared a proclaimed offender in a case linked to alleged controversial statements on social media, after he did not appear despite summons. Even if one disputes the merits of such cases, the existence of pending legal exposure changes incentives. It creates a strong reason to shift the conversation away from process and accountability and toward emotional headlines and international sympathy.

When you are dealing with absconding allegations or unresolved proceedings, the easiest place to fight is not a courtroom, it is the moral imagination of an overseas audience

This is why the role of advocacy groups and amplifiers matters. PWA amplified the Guardian coverage and helped lock in the preferred reading: targeted intimidation, foreign state shadows, dissident under siege. The Guardian itself wrote in suggestive terms about criminal proxies and a foreign state, while also noting that police were still examining motivations and links. That is a delicate line. A careful reader can see the caveats, but most readers absorb the insinuation, not the caution. Once the foreign hand is implied, Pakistan as a whole is put in the dock, even before a trial establishes facts.

To many observers, PWA does not behave like a rights body that keeps equal distance from party politics. It reads more like a narrative front, sustaining attention by monetising victimhood, packaging complex disputes into export friendly morality tales, and sheltering allied figures from scrutiny. That does not mean the attacks were not real, or that safety concerns are invented. It means the megaphone has a political angle, and that angle shapes what is emphasised and what is quietly ignored.

Responsible journalism has a different job. It should separate allegation from implication, and implication from proof. In this case, the basic news, that attacks were alleged, that arrests and charges have occurred, that counter terrorism police are involved, is important and should be reported. But responsible reporting should also resist the temptation to turn a contested political actor into a one dimensional emblem.

It should explain his political history, his institutional roles, and his legal context with the same energy used to describe the violence against him. Otherwise, journalism becomes a tool for career rehabilitation, not public understanding

None of this is an argument to downplay threats. Britain should protect residents from intimidation, and Pakistanis abroad should not have to live in fear. The point is narrower and more urgent: the public must be able to hold two ideas at once. A person can be a victim of a serious crime and also a political operator pursuing advantage. A state can have real governance and rights problems and still be unfairly demonised by simplistic templates designed for foreign consumption. When we accept prewritten scripts, we surrender the ability to ask adult questions.

If the Guardian and groups like PWA want credibility, they should welcome scrutiny rather than treat it as hostility. Publish what can be published, clarify what is not yet known, and avoid nudging readers toward conclusions that the courts have not reached. Evidence should lead, not framing. The UK deserves truth about threats on its soil, and Pakistan deserves to be discussed as a real country with institutions, conflicts, and facts, not as a cartoon villain that conveniently serves someone else’s legal and political strategy.