HOW PAKISTAN IS BUILDING A NEW TRANSPARENCY FRAMEWORK

The worldwide belief that corruption is widespread, systemic, and mostly unchecked has long accompanied Pakistan’s historical fight against corruption, posing an even more difficult obstacle. Important governance realities were once reflected in this narrative, which was shaped over decades by selective international commentary, media amplification, and inherited institutional weaknesses. But it is no longer consistent with Pakistan’s current course. Pakistan is currently undergoing major institutional reform, growing its digital governance, bolstering its enforcement systems, and bringing itself into compliance with international standards for transparency. However, despite quantifiable advancements, antiquated beliefs still obscure a change that is taking place in the administrative, financial, and regulatory spheres.

Examining citizen-level data highlights the discrepancy between perception and reality. There is strong evidence that public relations with the government is evolving, according to the National Corruption Perception Survey (NCPS) 2025. The long-held belief that corruption controls day-to-day bureaucratic interactions is seriously challenged by the fact that 66% of Pakistanis say they have never paid a bribe. The public’s perception of police services, which has historically been one of the least trusted sectors, has improved by 6%, which is equally noteworthy. These changes imply that rather than discretionary, individualized channels of influence, citizens are increasingly encountering structured, regulated service delivery.

People’s perceptions of the state are starting to change as a result of reforms that standardize processes, decrease in-person interactions, and implement digital audit trails

The results of enforcement support this changing governance environment. With total recoveries exceeding Rs 12.3 trillion, the National Accountability Bureau (NAB), which is often at the center of political controversy, has reported unprecedented results. The fact that Rs 11.4 trillion of this sum was recovered in just two years and nine months, a time marked by increased institutional vigilance, is even more startling. Accountability has transcended symbolism, as evidenced by NAB’s recovery efficiency, which returns Rs 643 to the national treasury for each rupee spent from its budget. These numbers demonstrate an enforcement ecosystem that is becoming more and more capable of recovering public funds that were previously lost due to poor management, rent-seeking, and illegal financial flows.

The international community has also formally acknowledged Pakistan’s transition to transparency. Its successful removal from the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) Grey List demonstrated the extent of internal reforms and was more than just a diplomatic achievement. Pakistan’s dedication to international compliance was shown through improved financial monitoring, stringent reporting requirements, better identification of suspicious transactions, and increased cooperation between enforcement agencies.

Beyond just improving Pakistan’s reputation, leaving the Grey List reaffirmed the country’s commitment to developing a transparent and safe financial system, which is crucial for national security, foreign investment, and economic stability

Pakistan’s extensive digital transformation is occurring concurrently with these institutional changes. One of the most effective methods for lowering human discretion, limiting unofficial influence, and producing verifiable, unchangeable records is digitization. The Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) is leading the way with reforms that automate tax filing, incorporate real-time point-of-sale monitoring, use algorithm-based audit selection, and enable online tax payment. These reforms reduce opportunities for manipulation and boost public trust in the fiscal system by discouraging undocumented transactions and reducing direct contact between taxpayers and officials.

Historically, one of the most vulnerable government departments, procurement has also seen substantial modernization. These days, e-procurement platforms create a transparent chain of documentation for each transaction by publishing tenders, accepting bids, and releasing results digitally. The availability of procurement data improves external oversight and internal controls while lowering the likelihood of partiality. Through standardized testing programs like the National Testing Service (NTS), merit-based hiring has spread throughout public institutions, decreasing patronage and guaranteeing competitive, open hiring procedures that appeal to a new generation of educated Pakistanis.

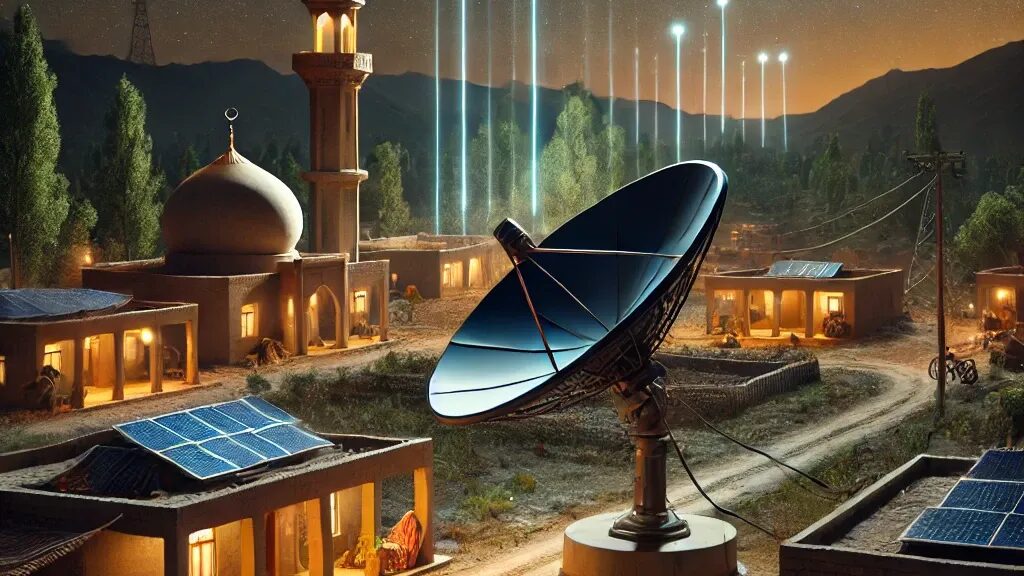

The nation’s social protection system is heavily impacted by digital reforms. One of the biggest welfare programs in South Asia, the Benazir Income Support Program (BISP), has switched to safe digital payments made directly to beneficiary accounts, doing away with middlemen and making thorough financial audits possible. The National Database and Registration Authority (NADRA), which has one of the biggest biometric identity systems in the world, supports this by offering precise verification for government services, banking, law enforcement, and welfare distribution.

The misuse of anonymous communication channels has significantly decreased, and national security has been reinforced by NADRA’s integration with the telecom industry, especially through biometric SIM verification

The State Bank of Pakistan’s regulatory modernization has also increased financial transparency. By reducing cash transactions, digital banking, mobile wallets, and online payments lessen the possibility of small-time corruption, and automated monitoring systems instantly identify big transactions. Accountability is further improved, and informed scrutiny of the banking industry is supported by public access to financial reports and regulatory updates.

Federal institutions are not the only ones undergoing these reforms. Digital audits, public dashboards, online complaint portals, and automated documentation systems have all been put into place by provincial governments. These developments lessen the possibility of arbitrary decisions and aid in the transition of governance culture from secrecy to uniform transparency.

Pakistan is changing structurally rather than aesthetically. Ministries are now more consistently releasing procurement data, audit results, and performance reports. Transparency is starting to be viewed by institutions as an operational standard rather than a burden. Pakistan’s governance landscape is changing as a result of this cultural shift, strong digital infrastructure, improved oversight procedures, and ongoing reform momentum.

The reality on the ground is one of data-driven decision-making, documented transactions, and institutional accountability, despite the fact that global perceptions may lag behind this advancement. Pakistan is well on its way to transparent and clean governance, and as reforms progress, they will have a greater impact on the nation’s economic recovery, social trust, and standing abroad in the years to come.